My First Funeral

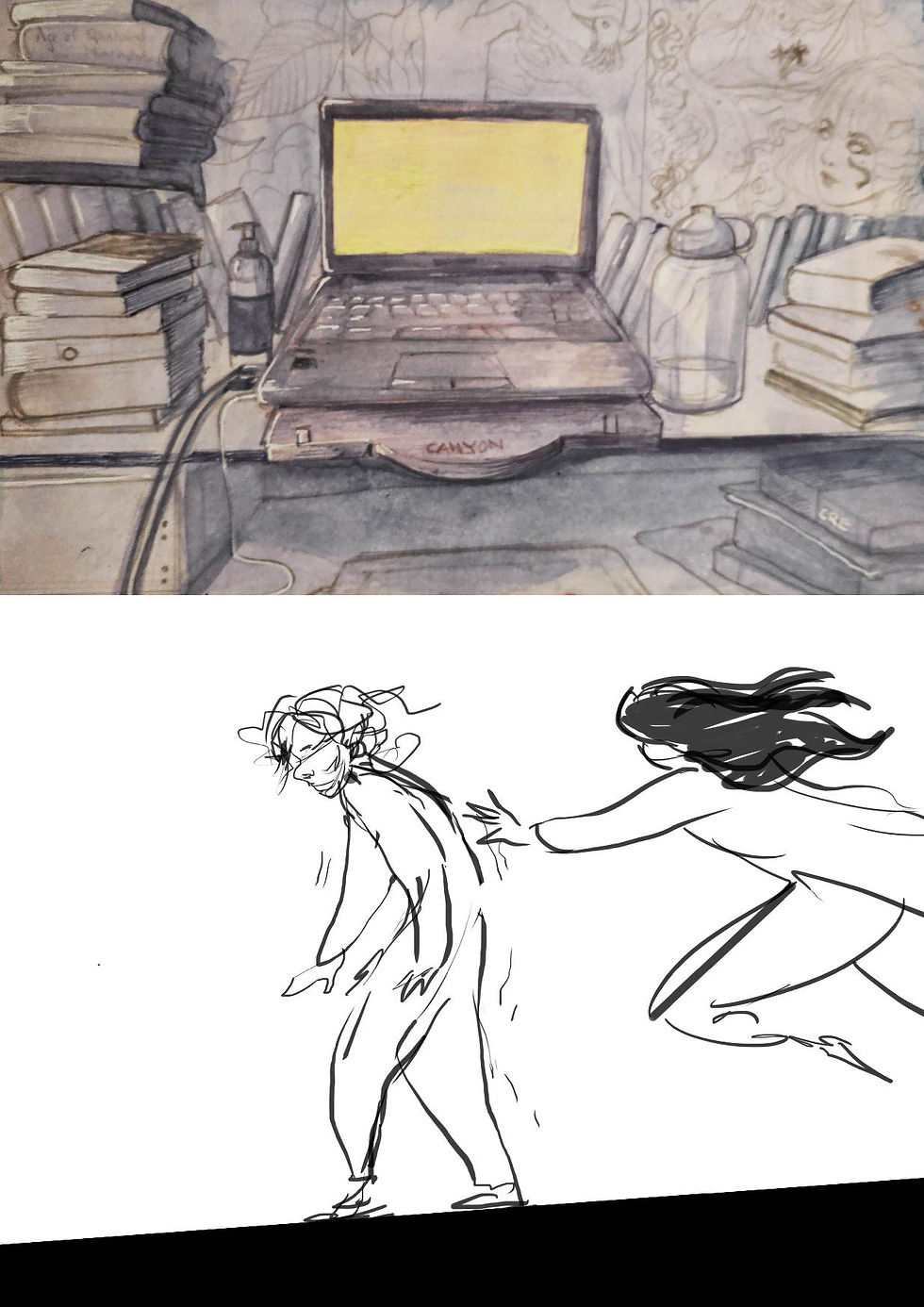

An animated memoir

“My First Funeral” is an in-progress film about my encounters with death, beginning at age 3, and how they formed my understanding of my relationships, my Muslim faith and my culture.

It is based on a personal essay I wrote to deal with a lifelong accumulation of unconfronted grief. The short is meant to assess the deaths of two of my grandmothers, both at different stages in my life.

Excerpts from the essay can be found here.

Watch the rough animatic

Concept art

The Fear I have Gathered from Funerals

An excerpt from my memoir on deaths in the family

When I was four my grandma slept on a mattress on the floor, because she couldn't climb into a bed. She was partially paralyzed. She’d become an unsmiling log that my family chugged around with very artificial cheerfulness. They’d pour canned orange medicine down her mouth, then tilt her head back so it spilled into her throat.

One morning I found ants on her fingertips.

“MOM.” My voice sounded like it came from someone else.

I showed her fingers to my mom. “Mom I think grandma’s dead.”

My mom smiled at me very brightly and her smile was so radiant that for a moment I forgot everything. She directed the unbreaking beam onto my grandma and said “Where’d all these ants come from? Let’s get them cleaned off.”

She brushed the ants off her fingers, which were going lilac blue. She helped her up and walked her to the bathroom. Eyes blinked in grandma’s frozen face. She would be alive until tomorrow.

The night she died was very hot. July. There was no electricity. It was Karachi’s era of power failures. All our doors lay thrown open into the garden, laying a path for cool air to enter and perhaps for her spirit to escape.

Sweating, I was asleep in just my panties. When I woke up the house was white. Sheets were spread on the floors, and an accumulation of date seeds sat in the middle of them. Scores of women were sitting there, hands raised in supplication, moaning Quranic verses. Siparas lay stacked in two columns- read and unread. I wandered outside and a woman in a white dress “shoo’d” me as if I was a wild animal. I ignored her but she gave me an intense angry stare and mouthed at me to go put clothes on. The gall. In my own house. Maintaining eye contact, I stepped over her dress with my small dirty feet and walked out the house towards the garden. What I saw made no sense to me.

My grandmother was naked. She was sat upon a bright red plastic stool in the lawn and all these women were crying and rubbing her up and down with a bucket and sponge. She was clearly dead- her eyes looked right through me.

After that I really don’t remember anything. Up until that point the memory is so clear that I feel like I can enter it and walk around. I swivel this way and that and see the house preserved as it was, with worn Persian rugs and chiki blinds and the “Titanic” dining table shoved off in a corner so women could sit in that space and count the ninety-nine names of Allah on their date seeds.

But after making eye contact with my grandmother’s naked corpse, I don’t remember anything. I barely remember her as a person as much as I remember her corpse. I don’t remember seeing my mom anywhere that day.

I fearfully imagine mom’s funeral sometimes, while she’s doing something mundane like scooping out the heart of a melon in the kitchen. Then I think, “I should have a child” because what if nobody worries for me like that? I think of how long it takes to find a man and worry I will never have a child. I have half a mind to ask a man, any man, for a child and then for him to leave. If I don't have a child, what if I don’t leave a hole in someone’s heart? My grandmother was the first hole punched through my universe- some divine hand shot in through my papier-mâché ceilings and snatched a chunk out. Every funeral since has been less of a shock.

The next disappearance was the girl on the leash.

My mother had a favorite tailor. Her shop was tucked between a trash dump and a school. I used to love going to her house because there was a fluffy white lamb tied outside the gate. It used to try to follow me home. Next to it an abnormally tall ten-year-old girl was also tied to a leash. Whenever I visited, she was positioned forward like an arrow, straining at how far the leash around her waist would go, but otherwise riveted still. Her grimy curls were cropped short. Her hands were bony, and sometimes she would pluck at her lower lip with limp fingers. Drool was always streaming from her mouth and she couldn’t form words.

Her mother, the tailor, always made her the most beautiful dresses. As I played with the lamb, I would envy them. I remember one- charcoal, with a full skirt gathered at her waist and blooming outwards. Black fabric roses around her neckline. Maybe I remember it wrong. I was always asking my mom for a dress like that one and she would always say “No, it was so ugly.”

A year later the girl was dead. At her funeral, the tailor was inconsolable with grief. I couldn’t understand it. I didn’t think she could have had much affection for a girl she kept tied up like an animal. The lamb was long gone too. They had eaten it. I thought of the girl’s dresses and wondered what would happen to them.

The girl jolts awake in me sometimes with her unseeing gray eyes. I think she started some freezing process in me. There is something about her case, as if I’m watching the world out of just one eye. Sometimes, I try to remember beauty to tether myself back to wherever I am, whomever I am with. I say sensuous words in my head- saffron, silk, green, beach, peach, embroidery, water on skin. But I can’t think that way for too long. I always return to the ugly things.

“You’re dissecting your feelings too much” my ex-boyfriend told me, gripping my jaw, heated, panting into my neck. “Let them wash over you. Don’t think ‘oh what’s this’ and ‘what’s this’. You do it constantly, and that’s why you can’t tell if you’re enjoying it!”

His brow was always furrowed even in half light, concentrating on me, a hand over my mouth so I wouldn't make a sound, so my mother in the next room wouldn’t know he was over. He wanted me to tell mom about us. He hated sneaking into my house at night. It made him feel ashamed. He wanted me in the daylight, before everyone. He liked listening to me talk, even when it was about deaths I was processing.

I thought, here was someone who would miss me when I was gone. Yet when I left him, not much of him remained with me. At least not as deep an impression as I felt I owed him. What I remember most is the purr of his anger under everything he said and did.

I left him because I was moving abroad. When I landed in America, I was ready to be brand new. It was summer in Rochester and there was a deer in my backyard. I had never seen a deer. I had the sensation of stepping into a dream. In that moment, I thought everything would change- but I’m the same.

Here too, I have nowhere to go. Americans speak English but it still feels like an entirely different language. There are gaps in between the English that I can fall through. The world I carry doesn’t translate right. It distorts. There’s a fine line between talking about home and painting myself as alien. Someone who went through something. Americans have got some sort of safety around themselves, or perhaps at the very least suffering of another kind. A softer kind, more often in the news than in their lives. Even the funerals here are reigned into parlors, with dress codes, with floral arrangements. Yesterday I met a therapy parrot, and a few days before a man in a Spiderman suit said he liked my haircut. A cashier encouraged me to eat fried crickets with him- for the experience. I run out of things to say to these good people reaching out. Something stands in between. If I want to talk about my grandmother’s funeral, I have to frame it in a way that lets people know what the strange part was- but will they get past the rituals? The date seeds and the names of God? I must script it right. It’s like rearranging a room before someone visits. I could erase the details. Or I could stay quiet.

When I can form a connection, it is often with people like me. And we can’t reach out to each other at all.

The third funeral was my mom’s uncle Zia.

End of excerpt